Carnival has two 'pulls' on the heartstrings of the Trinidadian. It is an expression of their cultural arts that defies comparison. In carnival, all at once, one saw the best of Trinidadian creative genius.

On the streets were the fabulous costumed creations, the 'mobile street art', the street theatre of the carnival bands, some of which has its origins in African 'masking'.

In the calypso tents one heard the passion and pain, the humour, the inventiveness of the calypso - an art form evolved through the need of the poor and downtrodden to express their soul, their wit and their amazing ability to survive and remain whole.

One also heard, in the pan yards of the ghettos and rural peasant lands the amazing sound of that musical wonder of the world called the steel band. These bands were made up of instruments forged out of the waste material of the cold industrial world that had come to Trinidad because oil had been discovered there, tuned and crafted to eventually emit some truly marvellous sounds.

Part of that 'pull' is also a deep understanding that carnival has evolved from a history of resistance, an insistence on humanness, on wholeness through systems of survival employed by the slaves and ex-slaves. In the music of the tamboo-bamboo and the subsequent steel bands were the ancient rhythms and melodies of their African ancestors; rhythms and melodies that harked back to their homeland and gave them sustenance during the dehumanising experience of slavery and colonialism, and helped to keep them whole and human. It fostered the 'in your face' declaration to the world that "we are alive - see we yah!"

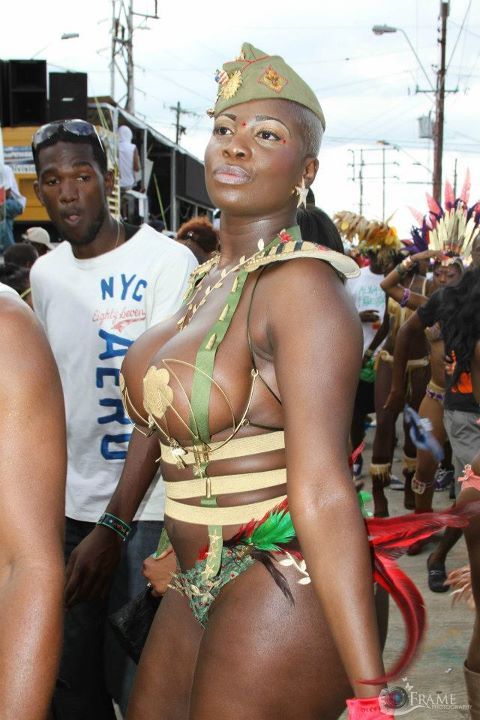

It is true that, over the past few decades much of carnival has been sold out to rampant capitalism and to the desire for quick gratification in the baring of flesh in skimpy costumes. Mark you, sexuality and sensuousness is an integral part of some aspects of carnival - as is so much of what is seen as black culture. But carnival is now marketed so much as pure 'wine and jump' and nothing else that the younger generation in Trinidad seems to have started to believe that and the older artistes of the carnival, like Peter Minshall, have begun to despair.

But the spirit of carnival is still alive and well.

And this is another part of the 'problem'. The source of the other 'pull' on our heartstrings.

Trinidad carnival has, from its birth, been fuelled by the spirits of the Orisha. The belief in the power of the African deities to sustain them through all hardship lurks somewhere in the souls of those who give the carnival movement its energy. This has been a conflict in the minds of the people of this highly religious country.

The problem lay in the fact that those who Christianised us taught us to reject anything that was connected to ancestral African religion as 'devil worship' and to be rejected.

Negative expression

So there was this ambiguity. How were we, as black people, to respond negatively to this expression of all that has sustained us through our darkest times? But then, how were we, as Christians, to embrace that which we knew had its roots in African tribalism and 'devil worship'?

Eventually, we grew to accept the idea that Orisha was just a religion which some of us no longer accepted, and carnival was not, in itself, sinful.

So, by the turn of the century, attitudes had changed to the point where David Rudder could have a hit calypso called High Mas in which he prayed to the father who had "given us this art" and who knew "the pain we're feeling", in his mercy, to "Send a little music, to make the vibration raise".

This would have been unheard of 50 years ago.

But Rudder, like most thinking people, also realises the excesses that take place at carnival time and the abuse of the spirit of the thing. This is why, in his calypso, he admits that " in this bacchanal season some men will lose their reason", and asks God to "Forgive us, this day, our daily weaknesses".

No comments:

Post a Comment